OVER-EXPOSED: Energy Poverty in Central & Eastern Europe

In five countries - Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Romania - EnAct investigates the causes and impacts of energy poverty with photos and text.

Among 28 countries comprising the European Union (EU), Bulgaria and Hungary hold the distinction of ranking lowest in terms of upholding the right—as stated in the European Pillar of Social Rights—to affordable energy as an essential service. A new report released by the Right to Energy (R2E) Coalition gives surprisingly high rankings to neighbouring countries of the Czech Republic (15), Poland (14) and Romania (13) (click links for country specifics).

Figure 1 • Ranking of countries based on the EU Domestic Energy Poverty Index (EDEPI)

“What gives?” many might ask. Until now, energy poverty has largely been considered as the problem of being unable to stay warm in winter, with extreme cases noted as families who may have to choose whether to ‘heat or eat’. The combination of harsh climates and low-quality buildings made it obvious that people in the CEE region would be particularly hard hit, even though hard data were often lacking.

Far from suggesting that conditions are not troubling in the Czech Republic, Poland and Romania, the new report gives equal weight to a factor not previously considered: being unable to afford energy for summer cooling. As a result, countries in Mediterranean climates and in the Baltic region have shaken up past perceptions.

Regardless of actual rankings, these CEE countries show ‘High’ to ‘Extreme’ levels of energy poverty and are known to account for a large share of the estimated >50 million EU citizens who cannot afford enough energy to support their health and well-being. Across this region, economic and political changes of the early 1990s are closely linked to rising levels of energy poverty. As energy markets have been liberalised, heavily subsidised pricing has been progressively brought in line with full-cost recovery levels. In parallel, people have little choice but to live in deteriorating residential buildings that lack basic energy efficiency requirements and household incomes are substantially lower than in most parts of the EU. In some regions, incomes declined during the recent economic crisis. For each country, the new report probes how four main factors—share of energy expenditures in total household budget, inability to achieve thermal comfort in winter or summer, or building condition—contribute to overall energy poverty.

Figure 2 • Weight of factors contributing to energy poverty in CEE countries

With climate change predicted to bring more cold snaps and heat waves across the EU, expected increases in demand for energy could drive many more people into energy poverty, including in the CEE region. A study by French investigators that compared energy poverty policies across five EU countries—France, Germany, the United Kingdom, Hungary and Poland—found that lagging policy and poorly maintained infrastructures in the latter two increased the need for actors from other sectors: non-profit associations, consortia, consumer groups, etc.

Social innovation to tackle energy poverty in the CEE

Taking concrete steps to eradicating energy poverty in this region is the focus of a new program, launched on 21 February by Ashoka and the Schneider Electric Foundation, to identify, support and scale up solutions that draw on social innovation. While recognising the importance of policy action to address this issue over the long term, Social Innovation to Tackle Energy Poverty seeks to deliver solutions that help people now.

In contexts of energy poverty, social innovation seeks to identify households that struggle to afford enough energy and understand their specific needs, and then implement actions that will improve their quality of life. The action should, directly or indirectly, help to ensure that they have better access to sufficient energy at affordable prices. In turn, reducing levels of energy poverty should bring about positive impact in society more broadly. The program highlights several areas of action (see Box 1) – and welcomes other approaches.

The underlying principle of social innovation is to introduce new approaches to seemingly intractable problems while also changing the social institutions that created such problems in the first place. The ultimate goal is to extend and strengthen civil society, and often involves commitment to open source methods and techniques. In many cases, social innovation also aims to involve multiple stakeholders in order to further develop existing—or foster new—cross-sector collaboration. Often, it is applied to tackle social and environmental challenges to improve things like living/working conditions, access to education, health and community development.

Areas of action on energy poverty:

The Solutions Accelerator program considers innovation across diverse dimensions vital to tackling energy poverty, with the following seven categories in mind. Social entrepreneurs active in different but related fields are also encouraged to apply.

For information on how to apply, visit the program website: www.tackleenergypoverty.org.

Bulgaria

Bulgaria’s low ranking on the EU Domestic Energy Poverty Index (EDEPI) reflects that high numbers of people report being both too cold in winter and too hot in summer. Additionally, a large share of buildings are of very low quality, which means they require more energy. At €216 per year, actual energy expenditures in Bulgaria are the lowest in Europe—in fact, only 10% of the €2 315 paid by people in Denmark. But because incomes fall well under the EU average, the lower expenditures account for a higher share of household budgets: energy bills eat up 14.6% of disposable income in Bulgaria against just 9.7% in Denmark or the lowest share of only 2.8% in Sweden with costs of €571 per year.

Photos: Emil Danailov

Energy poverty is not officially recognised in Bulgarian legislation and awareness of the issue is low among politicians, according to a 2014 report by REACH (Reduce Energy use And Change Habits). The only support currently offered is through the Winter Supplement Program (WSP), administrated by the Ministry of Labour and Social Policy, which provides financial aid to help pay heating, electricity or natural gas bills, or for the purchase of coal briquettes or wood. It is available only to households earning less than the guaranteed minimum wage and only for a period of five months. Anyone who has purchased property in the past five years or travelled abroad on their own expenses is ineligible. In 2013, more than 251 876 households received support through this program (the population of Bulgaria is 7.3 million).

On a positive note, Bulgaria has launched programs to improve the energy efficiency of homes. For multi-family buildings, through an Operational Programme for Regional Development, a budget of €25.6 million was allocated to cover 75% of the diverse costs associated with bringing buildings to a ‘C’ rating. To participate, all individual unit owners in a given building must demonstrate they can cover the other 25% of the costs.

More appealing (and more successful to date) is a credit line, which provides 20% of funding for energy efficiency in individual households and multi-family buildings. Between 2006 and 2014, more than 50 000 credits (adding up to €27.7 million) were approved, with new windows being the most popular action, followed by the purchase of air conditioners and wall insulation. The scheme was not very useful, however, to low-income households, who could not afford any additional costs or invest in energy efficiency. In effect, poverty itself was shown to be a barrier to energy efficiency.

Bulgaria does have legislation that protects people from being disconnected from energy services.

Czech Republic

Like other countries in the region, the Czech Republic has a legacy of poor thermal insulation in buildings and low energy prices due to subsidies introduced under Soviet regimes. In recent years, as subsidies have been phased out, household expenditures for energy have significantly increased: as a result, one report estimates that 16% of the population now faces energy poverty. To date, energy poverty is not recognised in legislation, but there are laws to protect people from being disconnected from energy services.

Photos: Anna Fotky

While poverty in general is low in the Czech Republic compared with other EU countries (e.g. unemployment has been stable at less than 4%), legislation puts those who rely on social housing at risk for energy poverty. The law allows private organisations to exploit generous state subsidies for accommodating people in need, but much of the accommodation provided is very low quality. In 2015, some 652 000 people received state financial aid for housing; of a total €455 million, 60% was estimated to be directed towards energy expenses.

Chance for Buildings is an example of a social innovation project that participated in a previous round of the Social Innovation to Tackle Energy Poverty program. An alliance of more the 300 companies across the entire value change of building construction and renovation, this network aims to improve the energy efficiency of social housing and to advocate for public authorities to promote energy efficiency in social housing legislation.

Hungary

Rates of energy poverty increased sharply in Hungary in the early 2000s, partially resulting from rising prices for imported natural gas, which about 76% of households have used for heating since the 1990s when the government sought to reduce reliance on firewood and coal. With low thermal insulation in buildings, however, energy demand is quite high. By 2010, an estimated 10% to 30% of the population was in energy poverty, and up to 22% of households were returning to heating systems based on firewood (20.4%) or coal (1.6%). An additional 11% of households used a mix of sources to help reduce heating costs.

Photos: Janos Kummer

The link between energy prices and incomes is evident: according to data from the Hungarian Central Statistical Office, between 1992 and 2010 nominal prices of domestic energy increased 13-fold while salaries rose just 9-fold. When faced with budgetary constraints, people who opt for wood over gas are clearly choosing lower cost over higher convenience.

The return to traditional fuels has negative implications for some Hungarian households: people must invest time in collecting and splitting firewood and are more likely to suffer health problems related to indoor air pollution. Surveys also show that some households maintain an indoor temperature below the 18°C to 20°C recommended by the World Health Organization, which can result in mild to serious respiratory and heart conditions. Others may opt to heat—and live in—only one or a few rooms of the house.

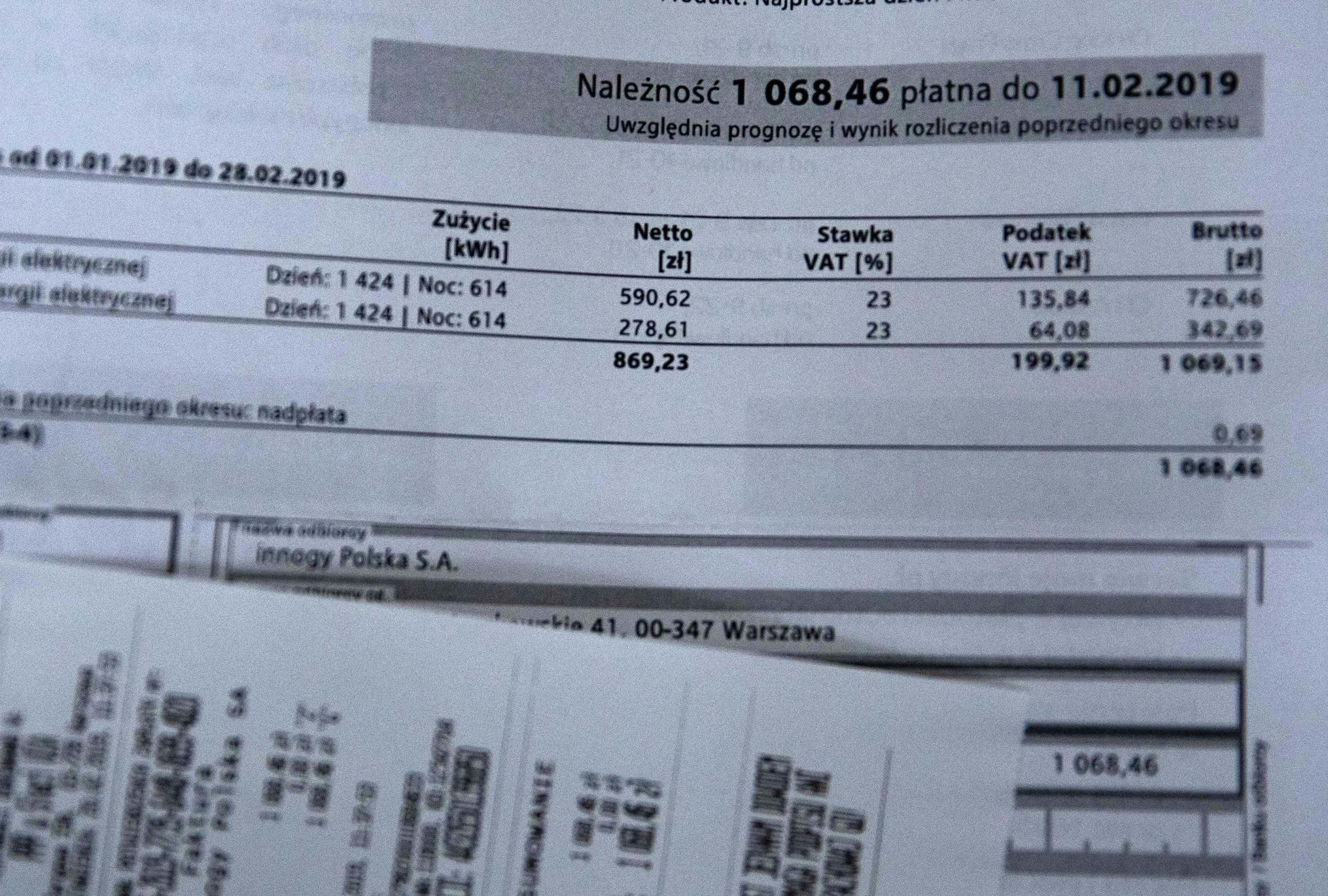

Poland

Estimates of the number of people facing energy poverty in Poland vary wildly: depending on the measures and methods used, figures of 10% to 45% of the population were reported in 2013. Rates are also vastly different in urban and rural areas: in cities with 500 000 or more people, the rate is between 3% and 7%. In villages of less than 20 000, it jumps to 17% to 32%, with those in the south-east region particularly affected. Often, a challenge is that only one or two elderly people, with limited incomes, live in houses built decades ago for large families. Typically, such homes have little insulation and inefficient heating systems.

Photos: Dawid Żuchowicz

Increasingly, policy makers in Poland recognise the need to define and address energy poverty through legislation; the 2013 Energy Law Act included definitions of vulnerable electricity and gas consumers. Additionally, at the national level, three forms of financial support are offered: a) housing allowances and energy supplements can partially cover relevant expenses; b) a thermo-modernisation grant can be applied to energy efficiency upgrades for individual homes or social housing, covering 20% of actual costs; and c) a special purpose allowance can be adapted according to need.

Diverse actors are engaged in addressing energy poverty in Poland with a strong focus on improving air quality (rather than energy efficiency) and training Home Energy Advisors to educate people on how to reduce energy consumption and costs. Among the public, awareness of available programs remains low. Despite a lack of coordination and low data collection, evidence suggests that the number of people affected is declining, from 28 400 households in 2006 to 7 100 in 2016.

Romania

While the recent EU Domestic Energy Poverty Index (EDEPI) places Romania at mid-range (13) among all 28 countries, experts in the country would be quick to point out that the phenomenon is poorly understood and data are seriously lacking. Ergo, current statistical estimates are likely to be far-removed from reality. In fact, the Romanian State’s methods for measuring poverty energy—taking account only of household income and home heating benefits—puts 4.6% of the population affected in 2015. Applying best practice across a widely accepted indicators, the experts say, would push the figure up to 19%. Some estimates suggest that up to 400 000 households, primarily in rural areas, are not yet connected to the electricity grid.

Photos: Bogdan Dinca

Law 123/2012 does define vulnerable clients explicitly as “…belonging to a category of household customers who, for reasons of age, health or low income, face the risk of social exclusion and who, to prevent that risk, benefit from social protection measures, including those of a financial nature.” With ‘income per household’ being the exclusive criterion to determine which consumers fit the vulnerable category, energy poverty remains unrepresented.

As a result, measures to reduce energy poverty that are applied in many other EU jurisdictions—such as protecting vulnerable consumers from disconnections for nonpayment, providing social tariffs, exempting certain components of energy bills or applying pre-assigned social benefits, as well as free counseling on energy-saving arrangements—are not offered in Romania.

At present, depending on income per family member (with low income defined as RON 55 per person), Romania grants financial assistance to cover a percentage of actual heating costs but applies a limit on average monthly consumption. Statistics show that 56% of the financing goes to the poorest 20% of households, while 70% of households in this income bracket receive no benefits. Similarly, while 12% of the population is eligible for social tariffs, some 42% of applicants do not qualify because their monthly consumption exceeds the cap. An additional data point suggests an urban/rural divide in assistance: at present, some 50% of the benefits is used to cover wood heating while only 2% is directed to households using electric heating. Finally, it must be acknowledged that in both rural and sub-urban areas, some segments of the population have no access to electricity or modern energy services.

As in other CEE countries, Romania will need to take large-scale action to improve the energy efficiency of dwellings to eradicate energy poverty. But to effectively roll out such measures, it first needs to acquire better knowledge of actual rates and distribution of energy poverty.