Health drives Irish fuel poverty strategy

Ireland has some of highest incidences of circulatory and respiratory conditions in the world. As no genetic link has been identified, the high rates seem rather to reflect the reality of climate and housing conditions: the first being 'cold and damp', the second being 'poor'.

Statistics also show that older people represent a high proportion of resources in the Irish health system, particularly in terms of hospital bed nights. In 2014, adults aged 65 years and over made up 12.7% of the population but accounted for 53.3% of total hospital in-patient care and approximately 36% of day case and same day care. Additionally, in a single month (February 2015), 86% of the 705 patients whose hospital discharge was delayed were aged over-65.

Analysis of such statistics suggest at least a significant portion of these health-care costs are associated with people being chronically cold at home, or trapped in fuel poverty by the combination of climate and poor housing quality.

The Irish government began tackling this problem through its first fuel poverty strategy, Warmer Homes: A Strategy for Affordable Energy in Ireland, launched in 2011. This strategy set out a vision to combat fuel poverty by making energy more affordable for low-income households, ensuring people could live in a warm and comfortable home that supported good physical and mental health and thus enhanced the quality of their lives. Since then, Ireland has spent more than EUR 2 billion on income support for people in fuel poverty and improved the energy efficiency of 140 000 fuel poor homes through targeted interventions. It also placed legal obligations on energy suppliers to ensure that they assist customers in fuel poverty.

In early February 2016, the Department of Communication, Energy and Natural Resources (DCENR) released A Strategy to Combat Energy Poverty, which applies 'expenditure on energy above 10% of household budget' as the method for calculating rates of fuel poverty. New research behind strategy confirms that up to 28% of households are at risk of energy poverty, a rate similar to the number of people living in basic deprivation. This indicates that energy poverty is not simply an 'energy issue' but rather 'a function of inadequate resources to cover the basic costs of living'.

A key aim of the new scheme is to gather evidence on the multiple benefits of energy efficiency. It will quantify reductions in energy bills, track the impact of the energy efficiency improvements on participant health and well-being, and the wider benefits to Ireland’s health system. DCENR has been working with the Department of Health, the Health Service Executive (HSE) and Sustainable Energy Ireland (SEAI) to create this new scheme.

Importantly, the scheme includes plans for a robust, independent evaluation of the outcomes.

Energy overview

As an island country on the periphery of Europe, Ireland faces substantial challenges in ensuring an affordable, fossil-free energy supply for citizens. With few domestic energy sources, Ireland relies heavily on imports to meet demand for its population of 4.7 million. In 2013, it had to import more than 90% of its energy supply (one of the highest import rates in Europe).

And what fuel is easiest to transport for heating purposes? Oil. So as oil prices peaked and the Irish Tiger economy spiked and then collapsed, fuel poverty increased rapidly between 2003 and 2013. Together with natural gas, oil for heating has gradually replaced use of coal and peat. The recent finds of gas reserves in Ireland are relatively small, and will affect the energy mix only moderately and only for a few years. The Corrib field, for example, will enable Ireland to use domestic supply for 60% of gas needs for about five years, but will be largely depleted in 15 years.

Until recently, domestic electricity sources were also extremely low: hydropower delivered only 0.5% of demand while other renewables (primarily wind) provided 6%. That left some 93% being delivered via underground and submarine cables from nuclear power plants in the United Kingdom. In 2014, the figure for renewable electricity increased to 22.7% and is expected to reach 40% by 2020. At present, more than 40 000 homes and 550 businesses use some form of renewable energy for heat.

The Irish government has set ambitious targets to have a low-carbon energy system by 2050 and to be completely independent of fossil fuels by 2100. This will require heavy upfront investments in re-designing the energy infrastructure. The best wind resources, for example, are located on the country's western fringes (where the energy grid is weakest), while most people live in central and eastern regions. The estimated cost of upgrading the transmission and distribution (T&D) network is EUR 3 billion. But weighted against imported fuels cost more than €6 billion a year, the government calculates the long-term gains provide good returns on investment.

Ultimately, the report says, this transition can only be delivered if people change their behaviour from being passive energy consumers to active energy citizens, where citizens and communities increasingly participate in energy efficiency projects that meet their local needs.

Empowering families through energy savings

Reducing energy costs can empower people to pay for other necessities such as food, clothing and medications.

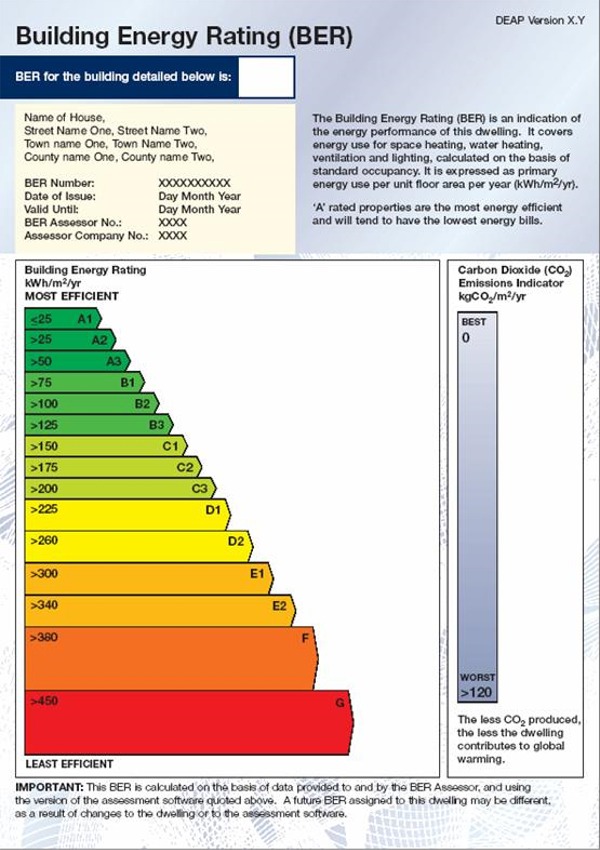

Building on data, knowledge and experience gained from the first affordable energy strategy, the Irish government can now demonstrate that improving the Building Energy Rating (BER) of a home from E1 to B2 can deliver annual savings of EUR 2 524 on a typical energy bill. For those in general poverty, freeing up EUR 200 per month is an immediate and substantial difference in the family budget. The strategy acknowledges that improving the energy efficiency of homes may not be enough to lift people out of fuel poverty (or poverty more generally), but it can drastically and permanently reduce their energy needs in a way that income supports cannot.

Responding to additional information gathered under the Survey on Income and Living Conditions suggests, the new strategy is also establishing a programme that will target lone-parent families, for whom basic deprivation andfuel poverty are particularly acute. To assist this population cohort in the near term, eligibility criteria for the Warmer Homes Scheme will immediately be expanded to include those in receipt of the One-Parent Family Payment and the Job-Seekers transition payment.

The government will also revise eligibility criteria so that existing energy efficiency support schemes are better aligned with indicators for basic deprivation and thus support the national social target for poverty reduction. Finally, DCENR and SEAI will enhance the Better Energy Communities Scheme to enable communities to develop new and innovative, locally-based solutions to energy poverty

Fuel poverty as a public health issue, energy efficiency as a cure: Warmth and Well-being

With a budget of EUR 20 million, Ireland's new strategy sets Warmth and Well-being as a core focus within the broader context of the Healthy Ireland initiative. It is designed to demonstrate that energy efficiency investments improve personal health, thereby reducing public health costs. This scheme will prioritise extensive energy efficiency upgrades to households in which occupants suffer from health conditions which could be exacerbated by living in cold, damp dwellings. This strong focus on health reflects international research that estimates the bulk (up to 80%) ofidentified benefits in addressing fuel poverty accrue in improved health outcomes and greater comfort levels.

The scheme will allow HSE staff to refer eligible patients directly to SEAI to receive deep energy efficiency improvements to their homes – essentially delivering a prescription to fix the cause of symptom rather than keep treating symptoms caused. In the first phase, a household will be eligible if one (of more) of the following conditions apply:

The service will involve installing energy efficiency improvements in the home to improve warmth, insulation, ventilation and heating, which will reduce energy costs and improve living conditions. SEAI-trained surveyors will determine the exact measures to be carried out. Importantly, the upgrades will be done at no cost to the household and contractors will minimise (to the greatest degree possible) any disruption to occupants.

Photo taken during a reportage in Ireland. COLD@HOME does not promote/endorse any particular products/services.

Each home and resident will be re-visited six month after the work is completed and again two years later to assess both the work carried out and any health status changes experienced by the occupants. This assessment, which will be carried out by an independent agency, will investigate aspects such as changes in hospitalisation rates, mortality, mental health and stress levels experienced by participants, aiming to quantify the changes against the cost of delivering the energy efficiency measures.

Promoting retrofits in rental and social housing

Low levels of energy efficiency are a particular challenge in the Irish rental housing market. The 2011 census found that 29% of dwellings in the country were rented, with the trend increasing.

Source: DCENR, 2016.

Other studies show that people living in rented accommodation are twice as likely to live in a home that has a BER rating of E, F or G, with about 20% of rented dwellings falling into the last two categories.

The new strategy recognises that such conditions contribute to both fuel poverty and poor health for occupants. For this reason, it seeks to overcome the problem of split incentives – i.e. the situation in which landlords bear the financial burden of investing in property upgrades while tenants benefit from lower energy costs.

The strategy includes a proposed roadmap for action, centred in large part on establishing (after 2020) minimum energy efficiency standards for rental properties. Acknowledging this would be one of the biggest changes to the rental market in the history of the Irish State, with substantial implications for small and large-scale rental property owners, DCENR will partner with the Department of Environment, Community and Local Government (DECLG) to hold public consultations on the roadmap. The consultation process aims, in part, to determine what grant or financing schemes would best help landlords meet such standards. In parallel, DCENR will run a pilot scheme to test such approaches through the Housing Assistance Payment (HAP) programme.

On the social housing side, local authorities are responsible for 144 000 homes, which are leased to those who cannot afford to buy their own homes. Rents for these properties are set by local authorities, based on an assessment of the tenant’s ability to pay (rather than a market-based rate). Estimates suggest 50% of these dwellings have a BER of D or below. Moreover, 60% of local authority tenants are either unemployed or retired, suggesting they likely have limited financial resources. Each year, the Energy Efficiency / Retrofitting Programme and the Returning Vacant Properties to Productive Use (Voids) Programme have freed up capital funding for a range of measures to improve the standard and overall quality of the social housing stock. Since 2009, investments of over EUR 240 million have resulted in the upgrade of over 58 000 local authority homes to higher energy efficiency standards.

Beyond energy

Recognition of energy poverty as a societal issue (i.e. broader than energy) has prompted the Irish government to incorporate into its strategy several policies in related areas such as job creation, employment activation, a higher minimum wage and restoration of employment regulation orders. It also considers increases in child benefits, fuel allowance and the pensioners’ Christmas bonus.

By helping to tackle problems of health, well-being and social inclusion and their associated impacts, the strategy aims to bring much wider benefits to Irish society. By addressing fuel poverty, the government is both helping people to rise out of poverty and reducing strains on already-burdened health services. It will also cut the nation’s spending on imported fossil fuels while promoting domestic jobs that will make homes more energy efficient and boost the share of renewable energy.

Governance

Importantly, the strategy establishes new governance structures that better integrate action on energy poverty with decision making across government agencies. It promises to establish a Energy Poverty Advisory Group, which will be independently chaired, and will provide expert advice to the government on energy poverty matters. In addition, DCENR will host an annual public forum on fuel poverty, which will provide stakeholders with an opportunity to comment on and input into government policy.

View more content on:

EnAct is grateful to Ken Cleary, Energy Efficiency and Affordability Division, DCENR, for his assistance in preparing this feature.