Pennies make pounds

A town perpetually on the brink

Stand atop any summit of the hills surrounding Merthyr-Tydfil (South Wales) and you can't help but feel it is a town on more brinks than one cares to think about. In the valley ahead, a network of roads that twist, turn and take steep dives towards the River Taff. Behind, power lines stretch into the horizon, over coal and ore seams that once had the hillsides and the town below teeming with activity. Today, scattered handfuls of sheep and cattle move only enough to keep munching.

Photo: P. Madsen / EnAct

During the early days of the Industrial Revolution (1740s), these ore-rich hills fed four of the largest ironworks factories in the world and Merthyr became the biggest, wealthiest city in Wales. In 1844, just one factory produced 50 000 tonnes of railway track, helping open the overland route across Russia to Siberia. But the Depression of 1829 hit hard and the ironworks entered a slow demise, with much of it relocating to Ukraine where both coal and labour were cheaper.

The economy revived in the 1870s with increased demand for coal, but it was short-lived: by 1932 more than 80% of the men at one mine were unemployed and over 27 000 people had emigrated out of the city. Often, it was the wealthy industrialists who could see better opportunities elsewhere and afford to make the move.

Industry revived briefly during both World Wars, reflecting growing demand for iron and steel. With many men away at war, women accounted for a large number of the workforce – a stark contrast to almost exclusively male labourers in the ironworks. As the war ended, several companies saw the chance to move into a well-established town, with well-established factories. Hoover, the American appliance company, set up a plant to manufacture electric washing machines. Teddington Aircraft Controls soon followed suit.

An overarching challenge arose: the factories needed workers, and the workers needed houses. As in many bombed-out cities across the UK, local builders grabbed what was close at hand and built as fast as possible.

Which brings us to the odd relationship between steel and the fuel poor communities scattered around town in 2016, including in the community known simply as Merthyr.

Quick build, long-term consequences

"Merthyr has a very large proportion of houses that were put up 'temporarily' after the war," says Graeme Watson of the Housing Renewal Department, Merthyr-Tydfil County Borough Council. "The construction method was a quick fix: they cast a slab of concrete, threw in a few sticks of steel, and clad the structure with a bit of tin siding – effectively recycling material from the war, including fighter planes. The aim was to get houses up quickly and replace them once the economy revived – maybe in 15 to 20 years."

Photo: P. Madsen / EnAct

An even larger number of homes, also meant to have 20-year life-spans, were simply pre-cast concrete. Most, like the house of the McInnes family, are unlikely to have any insulation in the wall cavities.

The consequence is that many residents of Merthyr have grown up thinking it normal to be 'cold at home.' And almost all have had to manage their household budgets around energy bills that are high in relation to rather modest dwellings, even when fuel costs were relatively low. The intersection of high energy prices and the economic crisis pushed many over the brink, into outright fuel poverty.

An early scheme to improve housing, reduce fuel poverty

In 2009, with financing from the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF), the Welsh government was among the first governments to set up a large-scale plan to retrofit low-quality housing across the country. Known as the Arbed Scheme, it makes the case that strategic investment in energy performance of the housing stock creates 'wins' all around.

- Home occupants are more comfortable and have lower energy costs, meaning they have more disposable income to inject into the local economy.

- Borough councils, by facilitating the retrofits, foster the build-up on networks in the construction industry and help create new jobs in their communities.

- Local building and retrofit businesses secure additional work and gain skilled employees.

- The Welsh government wins in relation to the EU targets to boost energy efficiency and renewable energy, thereby reducing energy-related emissions.

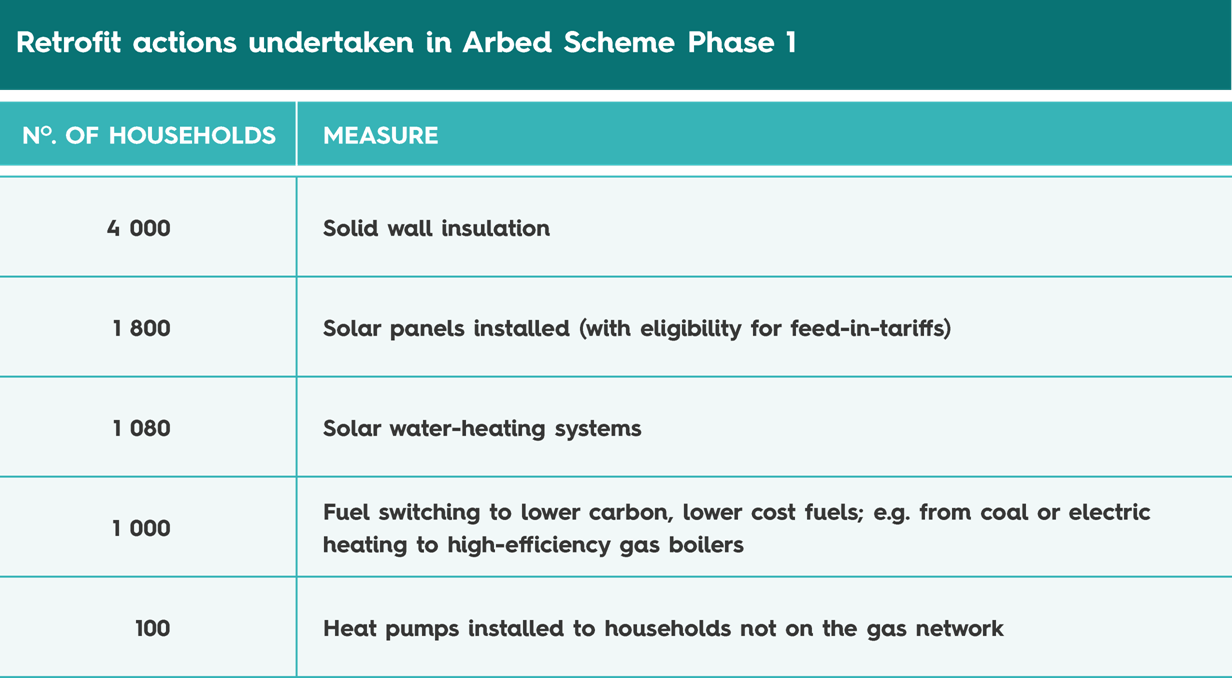

In Phase 1 (2009-12), the Government of Wales was able to leverage an initial investment of GBP 36 million to attract an additional GBP 28 million from partners such as social housing providers and local authorities. Recognising the opportunity to benefit from cost savings and economies of scale, some private sector players joined the scheme. Energy companies invested a further GBP 10 million to help satisfy their obligations in relation to Carbon Emissions Reduction Targets (CERT) and Community Energy Savings Programmes (CESP). With these investments, Arbed Phase 1 funded measures to over 7 500 households in Wales.

Rolling out at scheme at the local level was core to the government strategy, anticipating the initivaite would thus boost local economies. Assessment of Phase 1 demonstrates success. Of 17 products used on a large scale, five are manufactured in Wales, which made the companies eligible for Arbed support. This helped develop local supply chains in low energy technologies and energy efficient measures. Forty-one out of 51 installers that delivered Arbed measures operate primarily or solely in Wales, while several of the remaining companies employ large numbers of people in the region. Additionally, the number of people with accreditation to install renewable energy technologies grew steadily.

Arbed Phase 2 (rolled out from 2012 to late 2015) involved investments of GBP 45 million, with GBP 33 million coming from the EDRF (results are still being analysed).

Community approach reveals specific challenges

Standardisation of both energy efficiency aims and methods to achieve them proved a central element to the Arbed success story. But Watson confirms that Merthyr-Tydfil had some context-specific challenges. The Arbed partners knew the steel frame homes, which number in the hundreds, to be "the most energy-inefficient house that could possibly exist."

What they couldn't anticipate was the degree to which the combination of moisture (the pervasive weather condition in the valley) and oxygen might have triggered the electrochemical reaction that causes steel to corrode. The resulting rust has a volume six times that of the original material, leaving the integrity of the built object seriously compromised. In effect, the contractors didn't know whether each house would be a relatively simple retrofit, or a major structural rework.

"Before you remove the outer shell, you have no idea what shape the steel will be in, so it is impossible to assess the true cost in advance," says Watson. "In fact, you don't even really know if a house warrants a retrofit."

In cases where the degradation was extreme, Watson had to accept the recommendation that the owners be informed their house is structurally unsound and unsuitable for the retrofit. More difficult was a situation arising from the fact of most steel frame homes being semi-detached. Heavy corrosion on one side was making the home unstable; if it collapsed, it would take the other side with it. Hence, the both sides were deemed unfit for retrofit.

Having completed two estate projects of more than 100 homes each, Watson can now calculate an average price. Replacing 300 mm to 400 mm on the bottom of each steel leg leads to a cost of GBP 3 000 to GBP 4000. This drives the total cost up to about GBP 14 000, compared with GBP 10 000 for deep retrofit on a standard concrete home.

As the Arbed Scheme generally aims for a cap closer to GBP 8 000 per home, it is most difficult for Watson to get funding for the most inefficient homes in his community. He can use 'secured' base funding from Arbed to attract other investors, but Arbed generally wants him to demonstrate 'secured investors' to meet the gap before approving the base funding.

"Value-wise, I think doing the steel houses offer a better return on investment than the concrete houses because they are so much more inefficient if left without retrofitting," says Watson. Moreover, he estimates that when the work is completed, the steel frame houses will last another 20 to 25 years. Without the retrofits, many will either fall over or need to be torn down much sooner.

Watson hopes the success of Phases 1 and 2 will make it easier to forge ahead in the next phase.

Partners carrying out retrofit work in Merthyr-Tydfil bumped into another artefact of the town's history. In one estate, all of the houses were previously owned by the coal authority, and still had coal back-boilers even though it has been impossible to get local since the last South Wales mine closed in 2008. In that case, the retrofit included an infrastructure initiative to extend a gas main to the community and installing high-efficiency gas boilers in each home.

Social gains from large-scale retrofits

As was the case in the McInnes' neighbourhood, many Arbed teams aim to make the work more efficient – and cost-efficient – by carrying out retrofits across a large number of houses in a single area. Allison Cawley, Project Manager for Melin Homes, has observed this approach has almost immediate pay-offs for the workers and the families getting work done.

"We typically enter a community by first looking for a club or association that already has good relationships with residents," says Cawley. "When you go knocking on doors to ask people if can disrupt their lives for a good cause, you need to be introduced by someone they already trust."

Once the work begins, Cawley says people often come out to watch and neighbours get to chatting and get excited about knowing their neighbourhood will soon look as good as those they've seen in information packages. Often, it stimulates collective action to clean up the neighbourhood in others ways, which can turn into long-lasting commitments to keep things looking good.

Yet in almost all communities, Watson (and many others agencies EnAct has spoken to) reports that a portion of the population decline the free offer, even when it represents a level of upgrades that would well be beyond the means of the residents.

"On the last scheme we completed, out of 190-odd houses eligible for upgrades, about 20 turned it down," says Watson. "In some cases, people had already undertaken substantial work on their own homes. Some came around once we explained that we would replace – at no cost – add-ons such as porch awnings or outdoor access ramps that have to be removed to install the external cladding."

Others are fundamentally suspicious of government schemes or of the suggested technologies because of scare stories they've heard through the grapevine. The truth behind such stories, says Watson, is usually that someone applied the wrong solution for the property in question.

Photo: M. Smith / EnAct

Unfortunately, those who decline can have a detrimental effect on a difficult-to-measure but significant aspect of the whole-estate approach. External wall-cladding can dramatically alter the overall appearance of a neighbourhood, resulting in a sense of community pride. Perhaps more importantly, it can change the perception of others who previously made negative assumptions about people in an area because the quality of housing had deteriorated. Once a street unveils its 'face-lift', the unaltered houses tend to look much worse by comparison .

Beyond better housing

In 2006, a Channel 4 documentary series ranked Merthyr-Tydfil as the third-worst place to live in Britain; in 2007, the town got bumped up to fifth-worst. A key factor is that Merthyr has the highest percentage of benefit claimants. As recently as 2009, Hoover (now part of the Candy Group) closed its last factory, prompting the loss of 337 jobs (it maintains its Registered Office in Merthyr).

"Job opportunities are extremely limited," says Watson. "Anyone leaving school would probably have to look elsewhere to find a job that might possibly provide everything they needed."

The Arbed Scheme is just one of the ways in which the Welsh government is making a good effort to stimulate the economy and improve social conditions. Over the next decade, the anticipated investment in housing retrofits is over GBP 1 billion, with a wider range of partners participating and leveraging funds from more sources.

Policy is playing an important role as the scheme develops. The Energy Act, for example, obliges landlords to improve the energy efficiency of their properties by 2018. The Green Deal and renewable heat incentives support the installation of solar panels and geothermal heat pumps while feed-in-tariffs ensure that excess electricity generated by individual homes can fed into the grid. For some households, shift energy from the 'cost' to the 'revenue' column in the household budget.

Photo: P. Madsen / EnAct

Dawn McInnes also received GBP 157 000 (over three years) to support the TAG Youth Club, which attracts 50 to 60 kids every afternoon it opens its doors. As she did with her sons Nathan and Callum, she's now teaching them how changing their behaviours can lead to better things.

"Some of these kids come from very difficult homes. If they understand what their mother makes on minimum wage and that the energy bill for a single week might be 40 to 60 pounds, they can start to see what choices she faces. 'What comes first? Do I put food on the table or do I put the heater on?' " says McInnes. "What I’m trying to say to them is that by just pulling a little bit back on how much energy they use, they can make it easier to have other things in their house."